Nijole

Early in the winter of 2019, Nijole became unwell.

She developed a chronic cough and a nasal drip, and over the following 10 months was wrongly diagnosed with chronic rhinosinusitis and treated with antibiotics. In total, Nijole had 25 medical appointments, but she wasn’t getting any better.

Kent is Nijole’s husband and has become her spokesperson.

“It had been months and that’s when I stepped in and said we need a chest x-ray. Ten months and they still wouldn’t listen. They just wouldn’t.”

The initial x-ray indicated Nijole may have lung cancer. The CT-scan that followed confirmed it. Eleven months after first seeing a G.P, Nijole finally had a diagnosis. The 63-year-old mother of three was terminal. The cancer had spread to her lymph nodes, spine, and pelvis.

“It was a hell of a thing. She was robbed of her future, and I was too. I was robbed of my future with her.”

“They said there was nothing they could do, but there was. It’s just that we’re 20 years behind the times in New Zealand. If we’d listened to the DHB, Nijole would be dead,” says Kent.

Up until her diagnosis in March 2020, Nijole worked full time as a horticulturist. She lived an active life on their remote Karamea property on the South Island’s West Coast.

That all came to a grinding halt when Nijole was told she had just months to live.

Lung cancer is New Zealand’s biggest cancer killer. Every year, more New Zealanders die of lung cancer than breast cancer, prostate cancer and melanoma combined. However, despite lung cancer killing more than 1600 kiwis every year, we don’t fund the first-line modern medicines to treat the disease.

The contemporary way to treat cancer is to identify a specific mutation or cancer biomarker in the tumour, and then personalise a patient’s cancer treatment with targeted therapies and immunotherapies.

It means that specialists can customise a patient’s treatment to specifically target their cancer. They no longer treat the disease, they treat the patient. In recent years, this has fast become the ‘standard of care’ for cancer treatment in our peer nations, but not in New Zealand.

Unlike Australia, targeted therapy and immunotherapy treatments aren’t funded here. Some languish on Pharmac’s waiting list. Others don’t even make the list.

Kent says New Zealanders need to understand how vulnerable they are to a health system that isn’t proactively telling patients about modern treatment options which aren’t available in our hospitals.

“I’ve spoken to shitloads of people with lung cancer who say they’ve been told nothing can be done. But there is. There bloody is. We just don’t fund it in New Zealand.”

Nijole has non-small cell lung cancer. More than a dozen genetic mutations have been identified in people with this form of cancer and, in Nijole’s case, she has EGFR or what’s called an epithelial growth factor receptor.

“They told us there were four medications suitable for Nijole but only one of them was funded, so she started on that one.”

Kent said they were told the treatment would extend Nijole’s life by a year but after that, there was nothing else they could do. There were no other drugs available on the public health system.

“They just tell you that you’re going to die but they don’t tell you that you can live with cancer. You can live with metastised cancer. You just have to get the drugs.”

“Nijole’s health really started to deteriorate in that year. She had an aggressive cancer and if we’d just carried on taking what we could get on the public health system, she’d be dead. That’s a fact. We would have been absolutely stuffed,” Kent says.

Nijole took the publicly funded drug Erlotinib for 11 months. It stops cancer cells from multiplying and can slow the spread of cancer, however some patients develop a resistance to the drug within a year.

“She lived with constant pain and tiredness and other nasty side effects. She got breathless walking up our driveway, something she could do easily before lung cancer, and couldn’t spend much time in the garden,” Kent says.

Meanwhile Kent had grown increasingly frustrated by his wife’s misdiagnosis and what he perceived to be apathy within the health system.

“The biggest thing that pisses me off is the arrogant culture of a lot of the doctors and senior staff in the DHBs. They talk to you like there’s no other option and as if you’re stupid. And it’s just bloody wrong.”

Kent says he will never forget the day a doctor told him to move on. He said Kent needed to put Nijole’s misdiagnosis behind him, and look to the future.

“He said ‘you need to move on from the fact that someone forgot to order her a chest x-ray’. I could have flattened him. I nearly did. And that is the level of crap you have to put up with from some of them.”

Kent, a hydraulic engineer before he retired, decided he would take the system on. He lodged a complaint with ACC detailing the eleven months it took to diagnose Nijole. ACC agreed the delay had contributed to Nijole’s late diagnosis, and poor prognosis.

The West Coast District Health Board was forced to apologise.

ACC now funds specialist care for Nijole who receives a combination regime of chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Since November 2021, Nijole has followed a treatment plan that is publicly funded in Australia including a combination of four modern treatments; Taxol, Paraplatin, Avastin, and Tecentriq.

Kent says the treatments are funded in Australia because they work.

“The medications she’s on are keeping her well, and she has a good life at the moment. She’s starting to get her colour back again, she’s eating more and doesn’t live with constant pain.”

He says Nijole’s last two scans have revealed her tumour has shrunk, but if it wasn’t for ACC “she would be buggered”.

Every three weeks, ACC pays $59,000 for Nijole’s treatment, but if Pharmac funded the drugs on our public health system for other sufferers, it would pay far less.

Our pharmaceutical procurement agency is skilled at negotiating a fair price for modern medicines, but the recent Pharmac Review revealed the entity’s strategy is antiquated and it is heavily focused on accessing cheap drugs. Saving money is the priority, not saving lives.

“Nijole’s prognosis is now 3–5 years, but our specialist has said that’s on average – and why should Nijole be average? As long as she’s breathing, there’s still hope.”

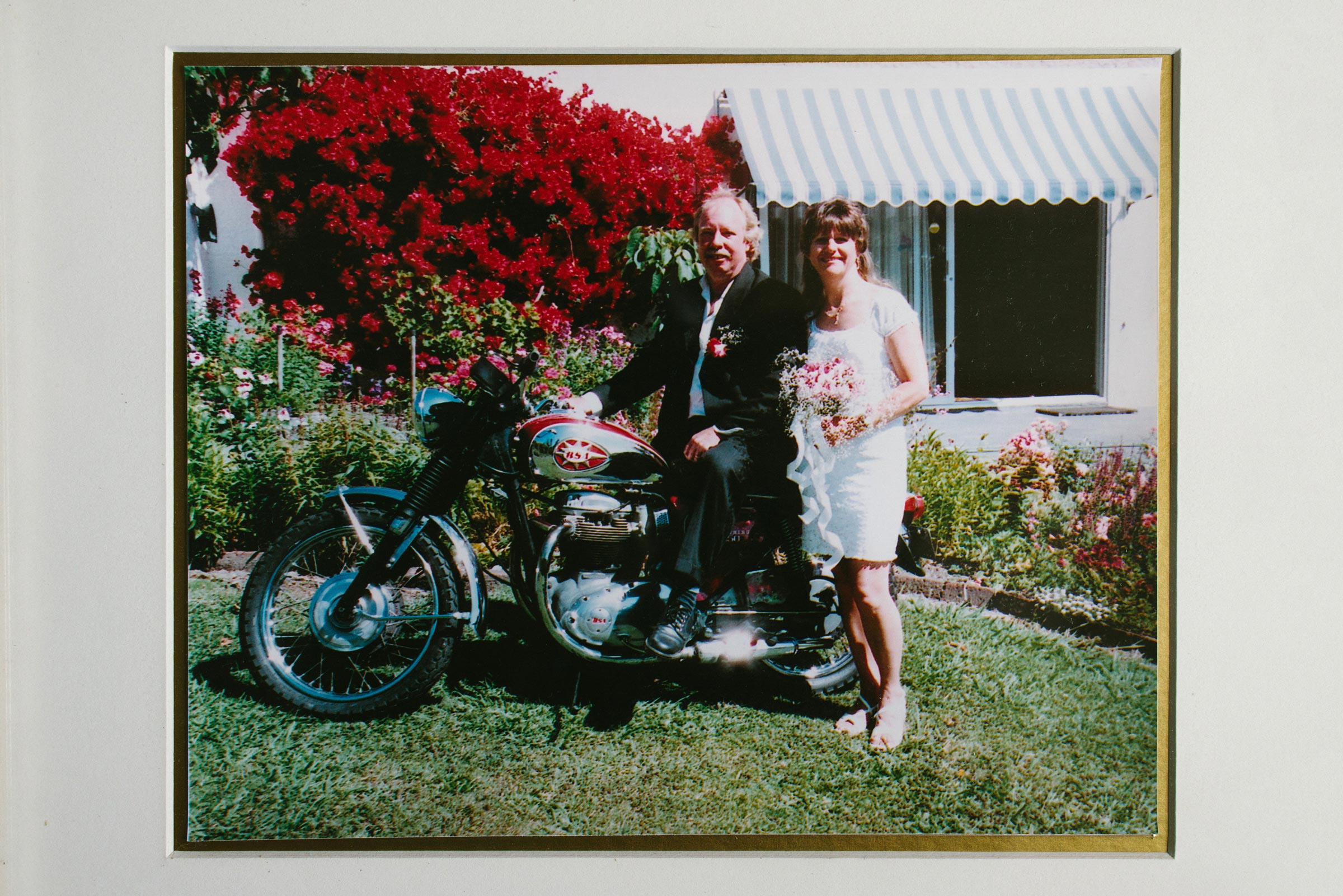

Nijole and Kent, who married in 2004, now travel to Christchurch for specialist care with Dr Rajiv Kumar at St George’s Cancer Care Hospital.

“Raj is brilliant. He’s an amazing man. Amazing.”

But it’s through these regular trips to Christchurch that Kent has discovered Nijole’s story isn’t unique. He recently met a 41 year old man at the cancer centre who could only afford one more round of privately-funded treatment.

“I heard him ask the nurse to squeeze the bag at the end because he needed every last drop of it.”

Kent talks of another man who had extended his mortgage by $100,000 to pay for his treatment, but his funding had run out.

“He told me that was it for him. The minute he stopped his treatment the cancer would take off again. It’s bloody sad. He can’t afford any more drugs so he said he won’t make Christmas.”

Kent says New Zealanders don’t understand that when you are diagnosed with cancer, you are not only fighting the disease, you’re fighting the health system too.

“We’ve had to fight for where we are now. We’ve had to fight for everything. When Nijole was diagnosed and wasn’t offered much in the public health system, we felt irrelevant. We felt as though they just wanted her to go away and die quietly, and not make a fuss,” Kent says.

“Nijole is alive because she’s had me to help her, but if she didn’t have me, she’d be buggered. You’re buggered if you have no one to help you fight this system. It’s wrong.”

In July, Kent and Nijole will fly to Australia to see her three children.

More than two years after she was told she only had months to live, Nijole’s alive and looking forward to seeing her family.

“She’s here because she got the drugs. If she was left to the DHB she would be dead by now, so what does that tell you?”

Kent’s dogged fight with the West Coast DHB has kept his beloved wife Nijole alive, but he says it should never have come to this.

“New Zealand is 20 years behind the rest of the world and that’s got to change otherwise we’re all buggered. Every one of us.”

Show your support.

Please share Nijole’s story.

New Zealand needs access now to modern medicines to treat lung cancer.

Related Stories

Let’s close the Gap

Get Involved1.

REFORM

PHARMAC

Achieve a measurable, political commitment to reform Pharmac and create a fit-for-purpose drug-buying agency that supports and enables greatly improved access to modern medicines – and ensure a direct line of political accountability.

2.

OVERHAUL THE FUNDING

METHODOLOGY

Introduce a globally accepted modern, cost-benefit analysis for medicines and medical devices which looks at the ‘value’ of a medicine, and considers the financial, economic, and social impact of untreated disease on our society.

3.

COMMIT TO AN OUTCOMES-BASED MEDICAL STRATEGY

Develop a Medicines Strategy to guide the decision-making process, create measurable targets to reduce Pharmac’s waiting list, and detail how the agency will respond to rapid developments in modern medicine to improve health outcomes for New Zealanders.